How do we choose where to take trips. One source was the Walt Disney

Show of 1955-6, which featured a series on the life of Davy Crockett. I was an impressionable 6-year old at that time. Like many others, I had a coonskin

cap and a cork popgun. Davy was my idol

and, in some ways, still is.

The Ballad of Davy Crockett

By Fess Parker (who played the role of Davy)

Born

on a mountain top in Tennessee (actually

born along the banks of a river not on a mountain top)

Greenest state in the land of the free

Raised in the woods so he knew ev'ry tree

Kilt him a be 'are when he was only three (he did kill many bears, but not beginning at age 3)

Davy, Davy Crockett, king of the wild frontier! (No one called him Davy – it was David)

Greenest state in the land of the free

Raised in the woods so he knew ev'ry tree

Kilt him a be 'are when he was only three (he did kill many bears, but not beginning at age 3)

Davy, Davy Crockett, king of the wild frontier! (No one called him Davy – it was David)

.

.

.

Off through the woods

he's a marchin' along (he was on the Natchez Trace)

Makin' up yarns an' a singin' a song

Itchin' fer fightin' an' rightin' a wrong

He's ringy as a be 'are an' twict as strong

Davy, Davy Crockett, the buckskin buccaneer!

Makin' up yarns an' a singin' a song

Itchin' fer fightin' an' rightin' a wrong

He's ringy as a be 'are an' twict as strong

Davy, Davy Crockett, the buckskin buccaneer!

The ballad goes on for

many a verse, extolling Davy’s virtues in an exaggerated or untrue form. One of the episodes of the Disney series

featured a rivalry with the notorious keel-boatman, Mike Fink (see Wikipedia on

Mike). Much of the tale is probably fiction, but it

did impress this 6 year old boy from western Connecticut.

Davy and Mike fought each

other on their respective keel-boats. Keel-boats

transported farm crops, whiskey and livestock down the Ohio and Mississippi

Rivers to markets in Natchez, Mississippi and New Orleans. During the era before steam power, there was

no way to easily barge upriver. The

barges (boats) were disassembled and sold as lumber.

The boatmen and women (if

the Mike Fink legend is correct) would walk back to Tennessee and Kentucky

along a series of woodland trails known as the Natchez Trace.

Besides playing Davy

Crockett, Fess Parker also starred in the TV series Daniel Boone. Age 84, Mr. Parker passed away on March 18,

2010. David Crockett died at the battle

of the Alamo in San Antonio, Texas in March of 1836.

The other source of an idea

for a trip were our friends and past travel companions (fall foliage tour

of 2008 and Lewis and Clark trip of 2014) Jim and Sandy Cooper. Sandy indicated that she wanted to see the Deep

South and some of the historic civil rights places in Alabama and Mississippi.

Following the

Natchez Trace starting from Franklin, Tennessee was to be the spinal column of our

trip. I say spinal column because we

took several side trips far off the historic Trace and extended it to New Orleans.

This will be a long

slutigram and I feel it is better

to organize the trip into categories rather than chronologically as they

occurred in history or even as we encountered them. The categories will be: 1. The Natchez Trace. 2.

Native American history. 3. Military historic sites on and near to the Trace. 4.

Civil Rights. 5. New Orleans.

6. Other interesting places. Several photos have text from signs. I recommend that you click on the photo to enlarge it to make reading easier.

1. The Natchez Trace.

The Natchez Trace is one

of many trails that provided a path through the trans-Appalachian forest. It is believed that many of these paths

followed those originally made by bison, elk and other large mammals. These paths were later used by the indigenous

Native Americans for hunting purposes.

As we found, evidence exists for very ancient human settlement along the Trace.

When the colonists first

crossed the Appalachian Mountains, it was often easier to travel by boat down

the Mississippi and then sail to the east coast colonies than to go over the

mountains. This was the era before the

use of steam power on the riverboats and before roadways into the wilderness.

The Trace winds its way

through 444 miles of forest from south central Tennessee, central Alabama

and western Mississippi, ending at Natchez, Mississippi. In 1801,

President Thomas Jefferson designated the Trace a national post road

for mail delivery from Nashville to Natchez.

In 1938 the Natchez Trace Parkway became a unit of the National Park

Service and the road was finally completed in 2005.

We followed the Trace

from north to south at the leisurely 50 miles per hour speed limit on a

well-maintained paved road beginning at Pasquo, Tenn. The scenery varied only slightly during the

first 200 or so miles. Large old trees

on both sides of the road was the normal view, with occasional points of

interest.

Our first stop was a

Birdsong Hollow where we appreciated the architectural beauty of the Double

Arch Bridge.

After 30 miles on the Trace

we exited and drove the short distance to the town of Clifton, Tenn. To see the

home of that well-known 11th President of the USA, James K. Polk.

Other than the White

House, this is the only remaining home in which Polk lived. When you read of his accomplishments as

President, you wonder why he seems to be ignored in so many histories of the

early USA. Read the text of this photo

(probably will have to enlarge it by double clicking on it) to learn that he was the

only president to accomplish all of his campaign promises.

From my viewpoint as a

stamp collector, his greatest accomplishment was this: the first adhesive US postage stamp in 1847.

The home has a very good

collection of articles and furniture actually owned and used by the Polk's

during their lifetime.

After an enjoyable lunch

at the Rockin’ Chair Café in Hohenwald, Tenn., we rejoined the Trace.

Few structures survive

from the era when the Trace was the main route of travel between Natchez and

Tennessee. The Gordon House built in

1817 does remain. Captain John Gordon

was a ferry operator on the nearby Duck River and fought under General Andrew

Jackson in his early battles for southern territory. This house was an inn used by the many

travelers along the Trace. As he died

shortly after completion of the house, we should give due credit to his wife,

Dorothea, who ran the inn and lived in the building until her death in

1859. There were inns every several miles along the Trace,

but this one is the only surviving inn from that era.

Shortly after the Gordon

house one comes to Jackson Falls, a secluded stream creates a scenic waterfall

accessible by a short walk through the forest. As it had not rained in the past few days,

the flow was low, but still a serene sight mixed with the sound of trickling

water. The falls are named after our 7th

president, Andrew Jackson.

We encounter the first of

the “Old Trace” areas. The Parkway

signage helps tell the story of the Trace and the various sites along the

parkway.

Except when we near the

cities of Tupelo, Jackson and Natchez, other traffic was a rare sight. When we turned into a parking area, we were

often the only auto in the lot. I suppose

during the summer it is used more. That

is one reason why we chose to travel during the off season.

Our next stop was the

site of a former inn, only a signpost now, at Sheboss. The story is that widow Cranfield and a quiet

man of American Indian heritage, who was her husband, ran the inn. When travelers would ask him a question, his

only response was “she boss.” The name

stuck.

A few miles south of

Sheboss we came to a site that gives closure, in a way, to our Lewis and Clark

trip of 2014. A memorial to Meriwether

Lewis. It is believed that Lewis

suffered from depression and that he took his own life here. Others insist that he was ambushed by

bandits; but the evidence does not support this theory. A great explorer came to an inglorious end

along the Natchez Trace during the night of October 11, 1809. During the Civil War, Confederate General Hood

removed the iron fence that enclosed the monument – he used the iron to make

horse shoes.

The Buffalo River crosses

the Trace near mile 380. A large flat

stone provides a hard bottom for the crossing.

It was said to look like a sheet of metal – thus the name, metal ford. The river is more like a large creek;

however, it might be more impressive after heavy rainfall. We walked along the portion of the old Trace

at the ford and enjoyed the quiet beauty of the forest during our stop here.

You might notice that the

Trace appears more sunken here than in the earlier photo, that is because as we

leave the rocky soil, the path wore deeper and deeper from all of the foot,

horse and wagon traffic of the early 1800s.

Once we get to loess soils in Mississippi (created by dust and silt

being blown in from afar) the path gets even deeper.

The Trace passes by

several mounds left by the mound-builder Native American culture. I’ll get to these in the Native American

history portion of this slutigram. Just

north of Tupelo, we encounter confederate graves and battlefields along the

Trace. These will be included in the

military history section.

Crossing the Tennessee

River the Trace leaves Tennessee and enters Alabama for 20 miles before

crossing the Mississippi State line. The

Trace takes us to Tupelo, where Elvis Presley grew up. Just before the city, the main Natchez Trace

Parkway visitor center is located.

Informative panels and helpful volunteers give a history of the Trace.

We enjoy two nights in

Tupelo, giving us the opportunity to restock snacks and do laundry. The city seems prosperous, with all of the stores

and food chains that we are used to seeing at home.

Along the Trace, we cross

the boundaries of 3 of the five Great Indian Nations, the Cherokee in

Tennessee, the Chickasaw and Choctaw in Mississippi.

Another 10 miles south

brings one to the strangely names place of Witch Dance. Read the sign and judge for yourself.

We have come out of the

mountains to a region with much farmland.

The parkway has succeeded in keeping a belt of large trees that usually

give the impression of being in a great forested area, but behind the trees, we

frequently see cornfields and pasture the further we go south in Mississippi.

20 miles south of Witch

Dance is Pigeon Roost. It is said that

the Passenger Pigeons were so numerous that they darkened the sky with vast

flocks in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Just for “fun” (not for consumption) many

would shoot them in large numbers, never realizing that their acts would cause

this bird to become extinct by the early 20th century. The last one died in captivity at the

Cincinnati Zoo on Sept 1, 1914. Today,

the forest is silent at Pigeon Roost. Learn more at: http://www.audubon.org/magazine/may-june-2014/why-passenger-pigeon-went-extinct

Our actual route took us

away from the Trace to Montgomery Alabama, but I’ll stay on the Trace for

consistency. After reaching Montgomery,

Elaine left us for a week, as one of her brothers passed away and she attended

his services in South Dakota. She rejoined

us in New Orleans a week later.

In my mind, the most

beautiful sight that I saw was the Cypress Swamp that is along the Trace near

the Pearl River at the north end of the Senator Ross Barnett Reservoir. As we entered the swamp, we all naturally began

speaking in whispers. The word “awesome”

is overused. Its meaning is creating a

feeling of awe. The swamp was an

appropriate place to use the word awesome.

Jim, Sandy and I spent quite a bit of time in the swamp, and were in no

hurry to leave it. I have one of the

swamp photos as a desktop background on my laptop.

The swamp was created

when the Pearl River changed its channel of flow. The Pearl River makes up part of the boundary

between Mississippi and Louisiana. If

one looks at the topographic map of the State of Mississippi, you will see that

much of the state is swampland, some of it being tributaries of the Pearl

River. When heavy rains fall, a good

part of the state can flood with disastrous effect. An interesting coincidence of no particular

significance is that the Pearl River’s length is 444 miles, which is the same

length as the Natchez Trace Parkway. We

watched the lazy river flowing and saw several locals out on the water in their

bass boats. I don’t imagine that much swimming

is done in the river, as there are alligators in the water.

As we near Jackson,

Mississippi (another place named after President Jackson), we cross what was

the boundary of West Florida. West

Florida is the part of the old Florida that was ceded to the British in 1763 by

Spain. It is comprised of the southern

counties of Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana east of the Mississippi

River.

The Trace skirts the

western edge of Jackson, MS, but you hardly get a glimpse of this state capitol

when driving the Trace. However, the

traffic gets pretty heavy until you get away from the city. Locals use the trace as just another way to

get from one part of the city to another.

Rather than go to Jackson, we went to Vicksburg for a few days. I’ll talk about that place in the military

history section.

The Trace highlights much

of the local American Indian history and civil war along this part of the

Trace. The old Trace exhibits its

deepest wear here.

Originally, we had

intended to stay in a plantation bed and breakfast in Port Gibson, MS. However, it was no longer a B and B. When we arrived in Port Gibson, we were quite

glad that circumstances prevented our stay there. We did not see one person or open business in

this small Mississippi town. Here is the

center of town which includes the county courthouse and requisite confederate

memorial.

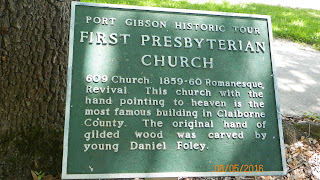

There was an interesting

church in the town, the 2nd oldest in the old southwest (at that

time). The steeple points to where your

focus should be in life.

West of Port Gibson,

along a narrow road we came to the Windsor plantation. In its day, it covered 2,600 acres of prime

cotton land. The exquisite plantation

mansion was completed in 1861. Its

structure was supported by 29 forty-foot tall columns. Even though the mansion was used by the

confederates as an observation post and by the Union forces as a headquarters

and hospital, the mansion survived the war.

On Feb. 17, 1890, a careless guest dropped their cigar ash onto the third

floor. The results can be seen in the

photo.

Before rejoining the

Trace, we pass the Springfield Plantation.

It is privately owned and is not open for tours. However, it has some historic significance; in

1791, Andrew Jackson married his beloved Rachel Robards at the plantation. Unfortunately, Rachel assumed that her first

husband was not among the living. He was

very much alive, and this blunder caused Andrew much consternation when he ran

for political office back in Tennessee.

Our trip along the Trace

only had 30 miles before reaching its culmination at Natchez. Near mile 15, is the restored Mount Locust

Plantation. Mt. Locust is maintained by

the National Park Service and is well kept.

We saw the opulence of other plantation homes and in town mansions, but

this was a modest home of a cotton planter.

A short walk from the

plantation house brings one to the slave cemetery. At least these unfortunates were given the

dignity of a burial place when their days of bondage were over.

Two miles down the Trace are the Loess Bluffs. Reading the sign helps one understand why the Trace has sunk deeper as one nears the Mississippi River.

Today we arrive in

Natchez on the Mississippi River for a three-day stay. Natchez was founded by the French in 1716 and

was known as Fort Rosalie.

Natchez gets its name

from the Native American tribe that had lived here for at least 1,500 years

before the French arrived to “found” the fort.

Let’s agree that the Natchez tribe or maybe an older group really

founded Natchez. The Spanish took

possession of the area in 1779 and named the town “Natchez” in 1790. The British actually took over from the

French in 1763 (at the end of the 7-years war, A.K.A. the French and Indian

War) and then ceded it to Spain in 1779.

The Spanish put some

effort into building a permanent town.

Several of the buildings in town date from the 1790s. Here is a residence, built in 1792.

While the USA was given

this land as part of the peace settlement with England, no one told the Spanish

that their city was now part of the USA.

Peacefully, the Spaniards lowered their flag and crossed over to the

west side of the River, which was still Spanish territory.

Natchez was Mississippi's

territorial capital.

It surprised me that there was and is a

thriving Roman Catholic and Jewish community in this Deep South city.

St Mary’s Cathedral:

Temple B’Nai Israel:

Not all the rest were

Southern Baptist, as evidenced by the large Presbyterian Church.

Natchez is located by the Mississippi River. During the

heyday of the Trace, it was the last main port on the river that was in

US territory. At that time, New Orleans

was in Spanish Territory.

Life in the country did

not offer the lifestyle that many planters desired. Many built their mansions in towns and cities

and left the running of the plantations to hired overseers. Natchez was a very wealthy city for these folk. Many of their mansions remain and several are

open for tours. Some at modest price

others seem to be a bit pricey.

We toured Melrose

Plantation home, which dates from 1849.

John McMurran (A Pennsylvanian)

arrived in Natchez in 1820. He practiced

law, was elected to the state legislature, married into a local family and

began acquiring five plantations along with their slaves. Melrose was to become the family home. Some said Melrose was the finest home in

Natchez. John had the money to build and

elaborately furnish his home.

House slaves had quarters

in two brick buildings behind the mansion.

A hidden hallway on the

first floor provided for unseen movement of all but a few serving slaves.

Elizabeth and George

Malin Davis purchased Melrose in 1865.

It remained in the Davis family until 1976. It was acquired by the National Park Service

(NPS) in 1990.

Our tour guide was a

university student who had quite an insight into this mansion, as his

grandfather spent the better part of his life as a butler to the Davis family

and he had told this young man many stories of how life was lived at the

mansion. By happenstance, later that day

we stopped at the Natchez Visitor Center.

It has some fantastic exhibits and a very good video. I was told that there was also a National

Park Visitor Center on the grounds. I

saw this very elderly black man (in his late 80s) in a National Park

Uniform. He must love his job, I

thought. Well, he was a retired NPS

employee. He told me that this was a

joint venture visitor center with the city and then asked me if we had toured

the Melrose. I said we had just had the

tour. He said his grandson was giving

the tour. If that doesn’t beat all, this

was the butler at the Melrose from many years ago. I asked him if he had some time to visit, he

said of course. I hurried through the

visitor center and found Jim and Sandy (Elaine was still away at her brother’s

funeral services) and said you have to come with me. We had a wonderful time listening to the

stories of old times at the Melrose.

This was a very special hour for us.

A blues festival was

being held at the time we were in town.

We attended one group’s gig and enjoyed the music.

So ended our time on the

Trace; but wait, there’s much more to tell you. The next section will center on Native

American peoples on our trip (some on the Trace, some not).

2. Native American history.

Some say it was about 15,000 years ago that the first

humans trod on the soils of the Americas; while others estimate it was 50,000

years in the past, and a few say it was even further back in the fog of

time. There were hundreds, if not

thousands, of different Native American tribes.

We encountered a part of the history of a few tribes along our

trip. I felt it was appropriate to put

these encounters in a section of their own.

This section will be organized on more of a time line rather than an as

we experienced them.

Within the eastern portion drainage basin of the

Mississippi River, a culture that has been designated “mound builders”

flourished for many centuries. Along and

near to the Natchez Trace there are many sites that were constructed by these

peoples. The distinguishing feature is,

not surprisingly, a large mound of earth.

Some contain burials, some artifacts and yet others, just a pile of

soil. Before they are cleared of trees

that have grown upon them, it would be tough to say whether a feature was a mound

or just a naturally occurring hill.

Aerial photography easily sorts this out.

An informative museum exhibit in Savannah, Tennessee

gives a good account of the culture of these peoples and displays some

exquisite artifacts.

A famous artifact made of red clay, the “kneeling man”

was found near to the town of Savannah, TN.

Analysis of the figure’s material revealed that it was likely carved in

the largest of the Mound Builders’ settlements in Cahokia, Illinois.

The many Indian Mounds we encountered were:

Bynum Mounds (mile marker mm 232), built between 1800

to 2050 years ago.

Pharr Mounds

(mm 287), built between 1800 to 2000 years ago.

Owl Creek Mounds (off the trace at mm 243), built

between 800 and 900 years ago and abandoned around 1200 AD.

About 800 years ago, a town occupied the high

Tennessee River bluff at the eastern edge of the Shiloh plateau. Between two

steep ravines, a wooden palisade enclosed seven earthen mounds and dozens of

houses. Six mounds, rectangular in shape with flat tops, probably served as

platforms for the town’s important buildings. These structures may have

included a council house, religious buildings, and residences of the town’s

leaders. The southernmost mound is an oval, round-topped mound in which the

town’s leaders or other important people were buried. The mounds are within the boundaries of the

Shiloh Civil War Battlefield, and escaped destruction for farming purposes

– a small benefit for the loss of life and limb that occurred here.

The largest of the mounds in this part of the

Mississippi Valley is Emerald Mound (mm 10), an 8-acre mound built between 1200

AD to 1730 AD. The mound is about 10

miles northeast of Natchez. It is the 2nd

largest mound of all known mounds; surpassing it is Monk’s Mound near Cahokia,

Illinois. Today, it measures 35 feet

high and its base measures 770 feet by 435 feet. On top of the main mound are two secondary

mounds, bringing the total height to 60 feet.

The mounds were built by hauling small baskets of soil and dumping the

earth on the mound. At long and tedious

task. There is a trail that allowed us

to access the top of the mound. As it is

a Federally protected site, you are warned by signage of the consequences of

disturbing the site. Many smaller mounds

were simply hauled away to fill low spots in the ground so that the land could

be easily farmed. The low spots were

often the holes where the soil had originally come from ages ago. Fortunately, we have many mounds that escaped

destruction.

Bear Creek Mound (mm 308), a later mound built between

1400 AD and 1600 AD. The information

sign indicates that the site had been inhabited for 8,000 years – but the mound

is of a more recent origin – so say the experts.

The Grand Village of the Natchez Peoples is located in Natchez. The site is preserved

by the State of Mississippi. They were

perhaps the last of the mound builders.

The site dates from about 700 AD and was still inhabited when the French

made contact in 1682 AD. The Natchez’s

downfall came when they attacked the French garrison at Fort Rosalie (which is

in Natchez) in 1729. The French were

really mad and eliminated these peoples and their village. It is believed that the few survivors took

refuge with other Indian tribes. This

brought the mound building era to a close.

There is a small museum on site, where further

information can be gleaned. Artifacts

recovered from the site are also on display.

It is not known what happened to the mound builders

and why the older mounds were abandoned.

The similarities to the Aztec stone buildings in central Mexico to the

dirt mounds seems more than coincidence to me.

Perhaps they migrated south?

During the most active use of the Natchez Trace, much

of the land in the southeastern USA was still in possession of what was known

as the Five Civilized Tribes of Native Americans. These tribes were the Cherokee, Chickasaw,

Choctaw, Creek and Seminole. Many of the

peoples of these tribes adopted the white man’s ways in terms of settlements,

agriculture, dress and even religion.

They believed all the treaty promises given to them by the federal

government. They did not suspect that it

was not adopting white man’s ways was not what was wanted. What was wanted was their land for

settlement. Truly a shameful part of USA

history.

As early as 1803, President Jefferson had predicted

that these peoples must be moved far away to the west. As the decades passed, settlement pressures

increased so much so that by 1830 the Indian Removal Act was passed by Congress

and signed by President Jackson.

However, in 1832, the Supreme Court said basically that this was not

legal. This ruling was ignored by

Jackson. In several waves, beginning in

1831, the greater part of the 5 tribes had been forced off their lands and were

relocated in Oklahoma. There was great

loss of life in the resistance to the move and in the move itself.

Our trip took us through the lands of the Cherokee,

Chickasaw and Choctaw. Near Tupelo, the

Chickasaw Capital was located along the Trace.

All that remains are a few signs and footing of their village buildings.

North of Jackson, Mississippi the Chickasaw boundary

with Choctaw lands is encountered along the Trace. All that remains of their presence is a

lonely sign along the Trace and in the place names of rivers and towns of the

area.

Cherokee lands were north of the Natchez Trace;

however, by happenstance, we stayed with a friend of Jim and Sandy’s who resides in

Vonore, Tennessee. In 1776, in the

Cherokee village of Tuskegee (present day Vonore) a remarkable man was born. We

know him as Sequoyah. He was the son of

a Virginia fur trader and the daughter of a Cherokee chief. He fought alongside of General (future

president) Andrew Jackson in the War of 1812.

During the war, he noted how the white man’s soldiers

could keep in touch with their families by writing letters home. Few, if any, of the Indians could read or

write in the white man’s language. After

returning home in 1814, he began the process of developing a system which he

reduced the thousands of Cherokee sounds into 85 symbols representing these

sounds.

In 1821, Sequoyah and his daughter introduced his

syllabary (not an alphabet) and within a few months, thousands of Cherokee

became literate. By 1825, the Bible had

been translated into Cherokee and by 1828 the “Cherokee Phoenix” newspaper

began publication. Sequoyah eventually

moved to Oklahoma and is believed to have died sometime between 1843 and 1845

during a trip to Mexico. Sequoyah’s

brilliance is represented by the quote:

“Never before, or since, in the history of the world has one person, not

literate in any language, perfected a system for reading and writing a

language.” The quote remained true until

Shong Lue Yang developed the Pahwah script for the Hmong language of Laos in

the late 1950’s.

During our travels, we visited several museums in

Tennessee, Mississippi and Alabama that gave further history of the early

peoples of these states. While Vicksburg

is chiefly noted for its role in the War Between the States, their museums also

feature the history of the Native Americans.

The Alabama history museum in Montgomery similarly has

a good portion of its exhibits focus on the early residents of the state.

3. Military historic sites.

We expected to visit several of the Civil War

battlefields along our trip’s route. We

found many of these sites and some other somewhat surprising sites of military

activity that was not of the Civil War era.

Twenty miles south of

Tupelo on the Trace, we find the general area where Hernando De Soto crossed

the future Trace in 1540. De Soto was a

Spanish explorer and conquistador who led the first European expedition deep

into the territory of the modern-day United States (Florida, Georgia, Alabama

and most likely Arkansas), and the first documented European to have crossed

the Mississippi. De Soto left Spain in

1520 and spent most of the rest of his years exploring and conquering in Costa

Rica. Nicaragua, Panama, Peru and southeastern North America.

Near to the Chickasaw village, noted in the previous

section, it is believed that DeSoto fought a battle with the Chickasaws, who

resisted his attempts to force them to be porters for his group. De Soto continued on his way and died of a

fever in 1542. It is believed that his

troops wrapped his body in a blanket and weighed it down with sand and then consigned

his remains to the Mississippi River.

The Spanish and French experiences in the Natchez area

have already been noted,

A big surprise was to find the restored Fort Loudoun

in Vonore, Tennessee.

This fort dates from the Seven Years War, known in

America as the French and Indian War. I

had no idea that battles from this long ago conflict had occurred in

Tennessee. The main thing we learned in

our history was about General Braddock’s defeat at Fort Duquesne and the battle

at the Plains of Abraham, just outside the walls of Quebec City (see slutigram on

the fall foliage trip in 2008).

During this conflict, Fort Loudoun was on territory

claimed by the State of South Carolina.

The various colonies had claims to western lands that extended all the

way to the Mississippi River. Several

claims conflicted between the colonies.

When the colonies became independent, this became a source of internal

conflict. All of the colonies

relinquished their claims with the adoption of the constitution in 1787.

Back to the fort . . .

To defend British claims to the Mississippi watershed,

a garrison from South Carolina marched into the future eastern Tennessee and

built the fort in 1756.

The Cherokee were allied with the British, but soon

the relationship broke down and the Cherokee attacked the fort in August,

1760. The British troops surrendered the

fort along with all of the armaments.

One of the actual canons has been found and was brought

back to the reconstructed fort.

The fort’s visitor center has several displays that give a

detailed narrative of the fort, its history and its reconstruction during the

1930s.

A monument to the War of 1812 is near the Natchez

Trace.

If you recall anything about this long ago conflict it is likely to be (1) during this war Francis Scott Key wrote the words to our National Anthem; (2) the British burned the White House, and (3) the Battle of New Orleans, USA’s greatest victory of that conflict was on January 8, 1815. Due to slow communications of that era, General Pakenham (British) and General Andrew Jackson (USA) were unaware that a peace treaty had been signed in Belgium on December 24, 1814. In today’s world of instantaneous communication, instead of killing each other, the battlefield would have been a place where the troops would have rejoiced and maybe even partied with the former enemy. Alas, more than 2,000 British troops, including 2 Generals were killed or wounded. American casualties were fewer than 20.

If you recall anything about this long ago conflict it is likely to be (1) during this war Francis Scott Key wrote the words to our National Anthem; (2) the British burned the White House, and (3) the Battle of New Orleans, USA’s greatest victory of that conflict was on January 8, 1815. Due to slow communications of that era, General Pakenham (British) and General Andrew Jackson (USA) were unaware that a peace treaty had been signed in Belgium on December 24, 1814. In today’s world of instantaneous communication, instead of killing each other, the battlefield would have been a place where the troops would have rejoiced and maybe even partied with the former enemy. Alas, more than 2,000 British troops, including 2 Generals were killed or wounded. American casualties were fewer than 20.

The Chalmette Battlefield is part of the Jean

Lafitte National Historic Park and is located on the eastern part of New

Orleans.

The reason for the one-sided casualty figures can

still be seen in the topography. The

British were attacking over an open field against entrenched forces of the USA,

who used cotton bales as protection. The

British could not get over the rampart and their bullets could not penetrate

the bales.

During our trip we encountered many sites of the

American Civil War, our most costly conflict in terms of loss of life than any war that

the USA has been engaged in. The causes

of the war were varied and can be traced back to the founding of the

nation. Two major results of the war

were the ending of the obnoxious practice of slavery in the “land of the free”

and the establishment once and for all that the dictates of the central

government were primary over the various states. One could spend a lifetime trying to visit

all of the sites of this war. In

Tennessee alone there are a few hundred sites of encounters. I’ll try to be chronological as best as I

can.

The first site visited never saw battle. From February 1861 to late May of the same

year the capitol of the confederacy was in Montgomery, Alabama. After the State of Virginia seceded from the

Union, the Capitol was moved to Richmond, Virginia. The First White House of the Confederacy was

the executive residence of Jefferson Davis and his family.

Surprisingly, the house was left standing during the

war and was fully restored in 1921. There are only seven stars on the flag, as that was the number of states that had seceded at that time. Eventually, 11 states withdrew from the union. Later flags have 11 stars.

Many of the personal items or Mr. and Mrs. Davis are

authentic.

Of course, we must give a nod to stamp collectors among

us and I did visit the First CSA (Confederate States of America) Post Office

headquarters in Montgomery.

A bit out of sequence here, but next to the White

House is the Museum of Alabama. It was

worth the visit and its admission cost is free.

There are exhibits about the state, its geology, American Indians, its

history from ancient times to modern day.

As far as military history, it had exhibits from the days of Spanish

occupation.

Buttons and uniforms of very early conflicts are on

display, as are many other items.

Ever been to Tangipahoa, Louisiana? Sounds like a Maori or other Polynesian name

to me. Camp Moore is located there

(www.campmoorela.com). This was a

training camp for soldiers during the Civil War. It was established in May of 1861 and

operated until Federal forces overran it in late 1864. After the war, the fort became overgrown with trees. Veterans of that conflict

came back at the turn of the 20th century and reclaimed and restored

the cemetery, where the remains of many of the 800 soldiers who died at the

camp are interred. Nearly all died from

disease or accidents.

The Camp has a small visitor center, staffed by

volunteers. Inside it are artifacts of

the war and the camp.

The main foci of the western theater of the War

Between the States (AKA the American Civil war) were twofold. Firstly, to deny the border states of

Missouri and Kentucky the opportunity to secede from the Union by stationing

troops in those states. Secondly, to

control the Mississippi River and several of its main tributaries, splitting

the Confederacy and denying it a means of transport and resupply of

provisions. The advent of the railroad

gave the Confederacy an ability to quickly move troops and artillery to where

ever enemy forces were massing. So,

besides control of the rivers, control railroad junctions also became an

objective.

A main railroad junction existed in Corinth, Mississippi.

By February of 1862, General U.S. Grant had

accomplished the first objective of removing Confederate forces from Kentucky

and Middle Tennessee. General Albert

Sidney Johnston had massed his troops at Corinth while General Grant began

landing his troops at Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee, just 22 miles north of

Corinth.

On April 6,

1862 the two forces met near the small country church at Shiloh.

Today that battlefield is known as Shiloh National

Military Park. However, Southerners call this the Battle of Pittsburg Landing. The visitor center has

the usual video and display that gives the history and importance of the

events that occurred during those two days of confrontation. Of the 66,000 Union and 44,700 Confederate

troops, over 23,000 were killed wounded or missing after two days of

engagement. That is nearly a 21%

casualty rate. Today we count our

casualties one by one; then they were counted in the thousands. Such is the waste and hell of war.

The area was heavily forested with some agricultural

fields. The battle was fought over a

large area as troops met in arms and then retreated back and forth. A paved road lets today’s tourist visit

several sites. Along the road are many

monuments and artillery pieces. The artillery pieces are from the war era, but

are not necessarily from the battle, as they were placed long after the war had

ended and there was no longer a use for these antiquated weapons of destruction.

The dead are honored differently. The Union dead were gathered and buried in a

central cemetery near the visitor center

An

all-too-common tombstone shows that the body interred below was

unidentified. Think of the anguish of

the families that were to never know if their son/brother/father/husband was

dead or alive or where or how they had died.

The Confederacy did not hold the field and their dead

are buried where they fell, often in a mass grave.

A rare event of warfare occurred when commanding

General Johnston was struck by a bullet that probably severed an artery in his

leg. He quickly bled to death. The site of his death is marked by a much

later constructed monument. President

Jefferson Davis and others had considered General Johnston to be his best

General.

Within one month Corinth was captured, thus denying an

important railroad junction to the South.

Our wanderings took us to Corinth right after our Shiloh visit. Corinth was a frontier town at the time of

the Civil War and was incorporated as a town in 1856. It had a railroad junction of an east-west

and north-south rail line and was thus a vital transport link that the Union

wished to sever.

A small visitor center has the usual flags, uniforms,

armaments, etc. and a pretty good video.

The fortifications of a part of the original defense of the town are on

this site.

After Shiloh, the town was overwhelmed with sick and

wounded southern casualties. On May 29th,

1862 Southern forces withdrew from Corinth, as they had not recovered from the

battle losses and the town was occupied by the Federal army. An attempt to retake the town occurred in

October of 1862, but failed. In January

1864, Federal forces abandoned the town, burning a greater part of the town on

their way out. While the federal forces

occupied Corinth thousands of “contraband” sought refuge there. “Contraband” was the word used to refer to

the slaves who were seeking freedom and protection from their former

masters. Many of these men subsequently

were organized into military units and fought with distinction during the

remainder of the conflict. Thus

disproving the common belief that the slaves could never make good

soldiers. A lesson that remained

unlearned until well into World War II.

Even at this late date (the 1940s), black troops mainly did labor

intense work, drove trucks or worked in military kitchens. Their prowess in conflict remained

unrecognized and was a source of ill feelings between black troops and the

military establishment.

By December of 1862, the Union advance into

Confederate territory had stalled on all fronts. On December 31st, 1862 through

January 2, 1863 the two armies battered each other near Murfreesboro, Tennessee

east of Nashville. The battle is known

as the Battle of Stones River. Another

battle, another visitor center and another cemetery.

The Union

forces were victorious, by the definition of victory at the end of the battle;

they held the field and the Confederates retreated. The casualties were: Union 13,249, Confederates 10,266. I’d say they both lost.

The remains of the earthen works defenses are

scattered throughout the town. Fortress

Rosecrans (the Union General) Brannan Redoubt is in pretty good shape and is on

a busy road in town.

Besides Sherman’s March to the Sea and the Burning of Atlanta, Georgia, the Vicksburg Campaign is the most widely known campaign in the Western Theater of the war. By late summer of 1862, only Vicksburg, Mississippi and Port Hudson, Louisiana blocked the Union’s complete control of the Mississippi River. Forces under General Grant crossed the Mississippi on April 30, 1863 and began a series of battles that culminated in the siege of Vicksburg.

One day after crossing the Mississippi River, Union forces routed the Confederates at Port Gibson.

The next encounter of any size was on May 12th

at the Battle of Raymond, which is on the way to Jackson, the State

capitol. A sign on the Natchez Trace

explains the battle and outcome.

A series of other battles led Grant's army to the fortifications at Vicksburg. Union forces made several attempts to seize the well-fortified town during the period after May 18, but were repulsed in every instance. A 6-week siege followed which ended on July 4, 1863 when General Pemberton surrendered. A few days later, the Confederates withdrew from Port Hudson. The Confederacy was now split down the middle and Grant had accomplished his goal. Soon after, he was given the command of the Eastern Theater of the War, as he fought and he won.

The town of Vicksburg and its battlefield are a must

see if you want to get a feel of what it was like to be under siege and to see

the lines of siege of the two armies.

First stop is, surprise! The visitor center of the battlefield.

On display are some unique items. Pictured from the battle is a cannonball embedded in a tree.

Portraits of the military commanders.

A 16-mile road winds along the lines of

engagement. Blue signs are for Union

units and Red for Confederate. Take your

time and stop at as many as you can to see where these brave souls fought and

died so long ago. We spent about a half day on the field.

The fortifications remain along with some artillery

pieces.

Long after the war, several states and other

organizations erected monuments to their fallen citizens. Most were erected before the last veteran of

that war passed away in 1959. In my

mind, the most impressive was the State of Illinois monument. Inside the monument the names of all the

fallen from that state appear on bronze plaques arranged by military unit.

Other state monuments include in this order Alabama,

Arkansas, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Texas and Wisconsin (there may be other state memorials, but I have no photos of them).

A recently added monument is to the African American

soldiers who fell here.

Associated with Vicksburg, but not part of the siege

is the Ironclad riverboat “Cairo” which was sunk while clearing mines on the

Yazoo River below the bluffs of the town of Vicksburg in December of 1862. Just as recounted about the Steamboat Arabia

in the slutigram titled Happenings April through July 2008, the Cairo was

encased in river mud which protected it from deterioration for 102 years. In 1964, the boat was raised from the muck

and has been restored since then. The

last time we visited Vicksburg (2003) the restoration was not at the stage

that it is now. You can walk the decks

and peruse the items found on the boat in a small museum at the site. The iron and wood you see are originals not

replicas.

Right across the road from the boat is another

National Cemetery, where Union soldiers are buried. The Confederates were left where they fell

and then unceremoniously dumped in mass unmarked graves.

After spending hours touring, we stopped at a local bakery and each had a cinnamon roll, yummy.

They each weighed 8 pounds (nearly 4 kilos) and were the size of a loaf of bread.

Truthfully, we just looked at the rolls in wonder.

The City of Vicksburg and its citizens suffered

through the 6-week siege. They dug caves

in the soil and lived there during Union bombardments. Food disappeared, as did pets, rats and all

sorts of vegetation during this time.

The Old Courthouse Museum has several exhibits focused on the war and

several on other history of the city.

Jefferson Davis was a resident of this county and began his political

career here.

Four rail lines converged at Chattanooga, Tennessee. The small town of 2,500 lay alongside the Tennessee River, making it an

obvious target for the next Union advance.

In September of 1863, Confederate forces withdrew from Chattanooga. Union General Rosecrans believed that this

was going to be a retreat to Atlanta. He

was surprised on September 18-20 when he was attacked in strength at

Chickamauga, Georgia which is within a few miles of Chattanooga. A small visitor center graces this battleground

and a loop road takes you through the historic area with monuments and graves

of the fallen. The picture of the

Spencer Rifle has quite a bit of relevance to the latter years of this

conflict. Up until 1863, Confederate and

Union forces had similar infantry weapons.

You shot one shot, then reload powder, wadding and bullet and then use a

ramrod to pack it all in before shooting another round and then repeat the

process. The Spencer Rifle was

introduced to some units of Union infantry.

It was a game changer, as you loaded 7 cartridges, after each shot you

simply moved the lever near the trigger.

This ejected the spent cartridge and loaded another one. Besides that, you could load 7 new cartridges

in less time than it took to load one round in the old rifles. Firepower was changed from a few rounds a

minute to dozens per minute, giving the Union forces a great advantage.

However, even with the Spencer, the Union forces were

put on the run back into the town of Chattanooga. For the next two months, the Confederates

held these forces under siege, as they held the high ground at Lookout

Mountain, just on the other side of the river.

Here are views of Lookout Mountain taken from Chattanooga and of

Chattanooga from Lookout Mountain. The

river loops around Chattanooga at Moccasin Bend. Any ships using the river for movement of

troops or supplies would have been shot out of the water by the artillery. During November 23-25, General Grant ordered

his troops to take Lookout Mountain and assault the strength of the Confederate

forces under General Braxton Bragg at Missionary Ridge. The conflict at Lookout Mountain became known

as the battle above the clouds. I don’t

know how the Union forces did it, but they fought their way up the mountain and

dislodged the southerners and then due to a mix up, the southerners forgot to

join their lines on Missionary Ridge.

Fortuitously, Union forces attacked in the weakly defended part of the

ridge and ended up dividing the Confederate forces. Bragg was forced to withdraw to Georgia.

Along the Natchez Trace, north of Tupelo, Mississippi

(mm 269) in the quiet of the forest are the graves of 13 unknown Confederate

soldiers. They likely died from battle

wounds from the battle at Tupelo or from illness.

More soldiers died from illness during the war than in

battle. While it cannot be known for

certain, the historical consensus is summarized below.

The

Union armies had from 2,500,000 to 2,750,000 men. Their losses, by the best

estimates:

Battle deaths:

|

110,070

|

Disease, etc.:

|

250,152

|

Total

|

360,222

|

The Confederate strength, known less accurately because of missing records, was

from 750,000 to 1,250,000. Its estimated losses:

Battle deaths:

|

94,000

|

Disease, etc.:

|

164,000

|

Total

|

258,000

|

Tupelo is known for a more famous event than its Civil

War battle which took place on July 14-15, 1864. The Confederates tried and tried to push the

Federals out; but the Federal forces could not be dislodged. By mid 1864, the war's outcome could no longer

be in doubt, the South was near exhaustion and its resources to continue

resistance were running low.

Much of the battlefield has been lost to development

in this somewhat prosperous city. A

small park (maybe a small half-block in area) on a main highway in the city and

another outside of town can be visited.

The final battlefield of this war that we happened on

was in Selma, Alabama. In the closing

days of the Civil War in April 1865, the fortifications protecting Selma were

thinly defended and quickly fell to the invading Federal troops. The only thing we saw was this one lonely

marker to note what had occurred here. This was not the last battle of the war (see slutigram Winter 2013 in Texas Palmetto Ranch), but the last battlefield which we encountered on this trip.

What was perhaps as interesting was that nearby was

another marker that commemorated the visit of the French General Lafayette to

Selma in 1825, 50 years after he had come to America to fight alongside General

George Washington. The last Surviving

French General who served in the American Revolution toured 24 states (which

was all of them in 1825) from July 1824 to September of 1825.

The final conflict site (we have had too many wars)

that we visited was the National World War II Museum in New Orleans. Elaine and Sandy decided to wander the

streets of NOLA (aka New Orleans, Louisiana) while Jim and I spent the whole

day at this museum. The sign explains

why the museum is located here.

Exhibits and videos cover 3 very large buildings. Jim and I went our separate ways and met up

at closing time. The museum covers all

the theaters of conflict where USA forces were involved. Betio was a battle on a small Pacific Island

part of the Tarawa Atoll, which today is part of the nation of Kiribati.

Only recently, it was in the news in September 2016,

were the remains of several marines found from this long ago battle and were

brought home to the USA. Several found

their final rest in Arlington National Cemetery. While it has become somewhat popular these

days to question why Truman dropped the atomic bombs on Japan. Some say the Japanese were going to

surrender, others dispute this. The

Japanese soldier would never surrender, preferring death to dishonor. Even after the bombs leveled Hiroshima and

Nagasaki, the military urged the emperor to fight on. Fortunately, the emperor said no, he would

surrender, thus avoiding the bloodbath that was estimated to cost at least

1,000,000 allied casualties and uncountable Japanese deaths.

Let us move on to other things.

4. Civil Rights.

Sandy asked that we include some of the famous Civil

Rights places from the 1960s. We focused

on Selma and Montgomery, Alabama along with a few other places in Mississippi.

Selma, Alabama was the home of at least 15,000 voting

age African Americans in the 1950s.

Through various methods, local officials were denying their right to

vote. To evidence this, only 156 were

registered to vote in 1961. Such skewed

statistics were all too common during that era.

In February 1964, Martin Luther King was asked to come to Selma to draw

national attention to this injustice. He

was jailed and wrote his famous “Letter from a Selma Jail” which helped ignite

outrage all around the USA. It was

decided to march on the capitol at Montgomery beginning at Selma near the

Edmund Pettus Bridge, an apt symbol of the racism of this area at that

time. The bridge was named after a

Confederate Civil War General, later a Democrat US Senator and Grand Dragon of

the Alabama Ku Klux Klan.

The National Park Service has two Interpretive Centers

along the route of the March, one in Selma and one about halfway to

Montgomery. We visited both places and

the Alabama History Museum in Montgomery to learn more about those troubled

times.

In Montgomery we spent some time at the Civil Rights

Memorial and Interpretive Center. Maya

Lin designed the memorial. She is the

same person who designed the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. Ms Lin uses the power of names etched in

stone and flowing water in this monument.

Montgomery is the state capitol of Alabama and it was

from there that Governor George Wallace made his attempts to resist the

civil rights movement.

In his final years, Wallace recognized the error of

his ways and became a supporter of Civil Rights for all citizens, but he had

caused much damage before that time. He

was the longest serving governor of any state at the time. Iowa Governor Terry Branstad broke his record

in 2014 when he exceeded 16 years in that office. Wallace also ran for USA President on four

different elections. In 1968 he won over

10 million votes and took 46 electoral votes, all from former Confederate

states.

In Mississippi we found several places relevant to

African Americans and to the Civil Rights Movement.

I found the story of Port Gibson especially

interesting. Port Gibson is a county

seat and numbers less than 1,600 in population.

It is 80% Black and is poor. The

other 20% are mainly white and many trace their presence back to the cotton

plantation era before the Civil War.

Protests during the Civil Rights era of the 1960s against local business

practices (most businesses in town were owned by the 20% white) ended up with a

boycott of these businesses. The owners

of which fired many of their black employees.

Many of the businesses then failed.

Today, it is a quiet town, with many shuttered establishments, a

casualty of the movement. We never saw

another person during our time in Port Gibson, just empty streets and

buildings, not even a stray dog was seen.

Natchez has a Museum Of African American Art and

History, with artifacts and artwork on display. As far as I can find, the Mighty Fire was not a racially motivated event. It is believed to have started from a carelessly discarded match.

5. New Orleans.

Four days were spent in New Orleans. It was nice not to have to travel long

distances for a while. Besides the WW II

Museum, we took in many of the sites of NOLA.

The mighty Mississippi is only a short distance from where is enters the

Gulf of Mexico. Traveling on an old-time

steam riverboat is a fitting way to see the environs of NOLA. The “Natchez” takes half-day trips on the

river.

Part of the fare covers a lunch while underway. The menu included fish, hush puppies,

etc. A fair meal, but nothing to brag

about. As we travel downriver, many

barges, ships and riverboats for the tourists are seen.

Various NOLA buildings, factories and an old damaged wharf

are cruised by.

We are told that the level of a major flood in 1965

can be seen in the discolored brick of the building pictured. You may have to click on this pic to enlarge it to clearly see the water damage line.

Sampling the local cuisine tickled our taste

buds. The Café du Monde (Café of the

world) provides the famous beignet, a deep fried dough-ball smothered in

powdered sugar. The pastry comes in a

paper bag. If you save the sugar

remaining in the bag, it can take care of your baking needs for weeks. This is one of the must go to places in

NOLA. Every tour group drops its

busloads here, with the result of very long lines to get the pastry and coffee. Another bakery sells beignets, about

a block away, for half the price and without a waiting line. I suppose the tour guides get a cut of the

sales for directing their charges to the famous site.

Elaine’s brother recommended that we try a meal at

Pascal’s restaurant. It is located in a

quiet suburb of NOLA. All of us were

glad that we took his advice. I had some Creole shrimp in brine along with a potato dish – yummy. Our bibs were a necessity if you wanted to

keep your clothing dry.

The French Quarter has many buildings dating back to

the 1790’s. Some are kept up well,

others not so much.

The Basilica of St. Louis looks like the Disneyland Castle. Inside, it looks like a European Church. Its history goes back to Spanish ownership days.

Music can be found everywhere. Solo and groups perform on the streets and in many of the restaurants. With so much competition, the quality of play is good.

The famous playwright, Tennessee Williams once lived

in NOLA and wrote several well-known plays while resident.

The above-ground cemeteries of NOLA draw the tourists

in by the busload; in our case, by the carload. St. Louis #1 Cemetery is listed

on the National Registry of Historic Places.

Our tour guide is professional and doesn’t dwell on silly ghost stories,

rather she explained the history of the cemetery, why the bodies are above

ground, how many can be entombed in one mausoleum, etc. Why above ground? If you were to dig a hole, within a few

inches the water table would be struck, making for a very messy situation not

amenable to sanitation.

If you read the dates on this grave, you can see that

the first person in this tomb took up residency in 1884, followed by several

more, as recent as 1994. Doesn’t it get

a bit crowded in there? We are told that

the heat and humidity reduce the remains to bones in only a few years. The bones are pulverized and dropped down a

chute in the structure, making way for the next burial.

The xxx’s are supposed to indicate that this person

was a voodoo priest or priestess.

Some crypts are owned by a family or an organization,

while others are merely rented out until the body can be put down the chute.

Some other crypts have just sunk or are sinking into

the soil and are no longer usable.

A lot was learned and a lot of fun was had during

these four days in The Big Easy. Legend

has it that the earliest use of the Big Easy had to do with the fact that there were so many

ways for a good musician

to make a living in New Orleans. Another possible origin for the nickname is

connected to the relaxed attitude toward alcohol consumption that was found in

New Orleans, even during the days of

Prohibition. The relatively low cost of

living in New Orleans, in comparison to many

major US cities, has also been suggested as the origin of the nickname. Take your pick or just make up another

reason. Bye NOLA

6. Other interesting places.

Not everything that we did and saw can easily fit into

my 5 categories. I’ll end this narrative

by citing some of these.

Trying to get a flavor of the south, we avoided chain

restaurants and sampled some of the local dietary fare. I tried mustard greens, turnip greens and collard

greens and found that, with butter, they all were palatable. In Vonore, Tenn. we toured Benton Hams, a

smokehouse, and were given some of their delicious product.

Little Doohey’s in Starkville, Miss. provided us the

opportunity to feast on local BBQ dishes and various types of greens. It is definitely a locals place, but they are

welcoming to tourists. The BBQ trailer is impressive, to say the least.

The rocking Chair Café in Hohenwald, Tenn. gave us a

nice mid-day break.

The Tomato place in Natchez is mainly a seller of

fresh vegetables, but they also sell delicious sandwiches. I did not try the boiled peanuts, as I have

tried them before and found them wanting.

Also in Natchez, the Bellemont Shake Shop, an old time

drive-in restaurant offers some fantastic milk shakes. There is no inside seating and credit/debit

cards are an unknown.

Weidemann’s in Meridian, Miss. was established in 1870

and is the oldest restaurant still operating in the State. Great food and reasonable prices. Cloth tablecloths and cloth napkins – nary a

bit of plastic to be seen. That’s peanut

butter in the bucket. You are encouraged

to eat as much as you like of it.

Surprisingly, I actually lost a couple of pounds on

this trip in spite of all the great restaurants.

While passing through Columbus, Miss., we spotted the

home of the playwright Tennessee Williams, whose New Orleans apartment we

stumbled upon later on. The home

reflects his humble origins

Speaking of boyhood homes, Tupelo was the home of one

of my favorite performers, the King of Rock and Roll, Elvis Presley. His home makes Tennessee William’s home look

like a palace in comparison. More Elvis

stamps. As the entrance fee was

exorbitant, we passed on seeing the inside of the home.

You may have seen this postage stamp picturing Elvis last year. This was the 4th time he has appeared on an U.S. postage stamp. He has appeared on hundreds of foreign postage stamps; most notably by small African and Pacific Island nations as a means to earn revenue from stamp collectors and Elvis collectors.

Near Flora, Miss. roughly 36 Million years ago a log

jam resulted in many trees being buried, they became fossilized and are now

part of the Mississippi Petrified Forest.

This called for a detour from our main route. A walking trail takes you through the forest

where the petrified logs are in abundance.

They have long been buried in the loess soils, but as the soil is weathered

away by the wind and rain out pop the ancient logs. Besides the trail, a rock shop exhibits many

gemstones to include phosphorescent stones.

Well worth the detour.

Some like it hot, especially on Avery Island, Louisiana. This is the home of Tabasco Sauce, the

product of the McIlhenny Company since it’s founding in 1868, still owned and

operated by Edward McIlhenny’s descendants.

A self-guided tour takes one through the process of how the sauce is

produced. A very nice gift shop is on

the property (surprise, another gift shop) where various hot stuff can be

purchased. Additionally, a restaurant

enables you to use some on their product on your meal.

All this hot sauce is making me thirsty, so I’ll end

this very long slutigram of our Natchez Trace and other places trip. Hope you enjoyed it. If you made it this far, congratulations. If a typo or two or incorrect info is

contained herein, please let me know so that I can make corrections.